Incunabula

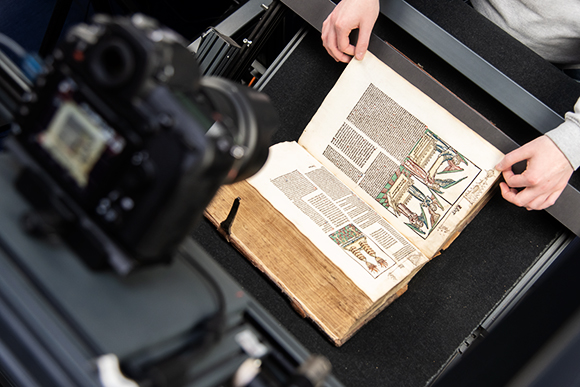

ULB’s holdings include more than 980 printed resources from the 15th century. Some of these resources, which are known as incunabula, are entirely unique, i.e. they have not survived at any other library. You can view these early testimonies of the art of printing in ULB’s Special Reading Room.

These testimonies to the early days of printing also include a number of fragments, such as a 30-line letter of indulgence from 1454 and twelve fragments of various donated editions. According to the latest research, ten of these are believed to have only survived in this collection.

ULB’s incunabula are listed in full in a printed incunabula catalogue (Inkunabelkatalog). Transferring the title records from this print catalogue to the online catalogue formed the basis of the work to digitalise the entire incunabula collection that began in 2011. These records can be searched there and used to request the originals.

All prints can be searched in the ULB catalogue and requested for consultation in the Special Reading Room. For more detailed information on ULB’s early prints, see ULB’s printed incunabula catalogue (Inkunabelkatalog). A great many incunabula have already been digitalised and are now available in ULB’s Digital Collections.

We have compiled a list of further search tools for you on a separate page. The originals can be consulted in the Special Reading Room under professional supervision.

In terms of the places of printing, the holdings are very much influenced by the acquisition practices of their previous monastic owners, and therefore strongly regionally influenced by the Lower Rhine area. The majority of the incunabula come from Cologne; indeed, alone 80 incunabula were printed by Ulrich Zell, who was one of the first printers in Cologne. Prints by other printers of particular note include a complete coloured copy of the West Low German Cologne picture bible (‘Kölner Bilderbibel’; GW 4308) and an extremely rare copy of the first edition of Wierstraet’s history of the siege of the city of Neuss (‘Geschichte der Belagerung der Stadt Neuss’). Overall, the prints are often from cities located along the River Rhine (as far upstream as Basel), but also the whole of the Netherlands.

Of the places of printing, especially the eastern Netherlands are popular. Indeed, 55 incunabula come from Deventer alone. The Upper German printing locations (with the exception of the Upper Rhine) are far less represented than would normally be expected in a German collection of this size. The percentage of incunabula printed in Paris is very high for a Rhenish collection. Of the Italian printing locations, Venice is the commonest with more than 70 incunabula. Among them are four prints by Johannes Manthen von Gerresheim, who was important for Düsseldorf and printed together with Johannes de Colonia. Very few of the incunabula were printed in other Italian cities.

The ratio of Latin to vernacular titles is even more skewed in favour of Latin titles than the ratio assumed by researchers for all of the incunabula. Among the titles in the vernacular, the relatively high proportion of Low German texts (including West Low German, which is close to the Dutch “Oosters”) and the relatively low proportion of High German texts is striking.